AI and storing data

Image generation

Generative AIs are able to create images seemingly out of thin air by taking in a prompt, describing a desired scene and outputting an image of that scene. Examples of this are Dall-E, Midjouney or Stable Diffusion. The obvious “secret” here is that these models have been trained on millions of existing images tags/text/descriptions of what is visible on these images.

Oversimplified, what you do is, after training on images you invert the direction of how the model is used. You input describing text (aka “the prompt”) and the model will create a probable but random image for this text. An adversarial network will check that only result with enough likelihood of being a good or valid result for the prompt will be presented.

Internally, these models actually denoise (i.e. “inverse diffusion”) an image from pure noise while taking “hints” from your prompts. When the model was trained, it learned what desired images look like and which prompts are expected with that image.

DALL-E imagening cats riding a bike

DALL-E imagening cats riding a bike

In other words, the ML model contains knowledge of what we will probably accept as an actual image to our prompt.

We will continue to oversimplify a lot in this posting. Please bear with me :)

Using an ML model to compress data

It is also possible to use the knowledge stored in an ML model to recreate an existing image.

Matthias Bühlmann demonstrates using StableDiffusion as a lossy image compression technology, similar to JPG.

Demonstration of using StableDiffusion as image compressor - (c) Matthias Bühlmann

Basically you translate and reduce (encode) the image data to a lower dimension (i.e. minimal amount of data), so that the StableDiffusions model can recreate the original image from the encoded data with minimal error. The reduced data is called latents. See variational autoencoders.

Internally a diffusion model is used again. But this time we do not start at random noise, but with the latent data (and some noise). No other prompts. As we created the latent data using our input image, our image has more or less become our prompt.

The reconstruction (decoding) process is basically the same as with the generative AI, but using the latent representation of the original image as source. Also no adversarial AI is used.

Diagram of encoding to latents from Wikipedia

Diagram of encoding to latents from Wikipedia

From a user’s perspective this creates the same workflow as using any (lossy) image compression technology. The image and the reconstruction are not identical, but look very similar to us. And the compressed image is is to transport.

Large image file goes in, small file comes out. Just make sure you have the same ML model to recreate/view the image. :)

Reconstructing 3D data

NVidia recently presented a technology called NeuralVDB with comparable traits on SIGGRAPH 2022, but for moving 3D voxel data - not static 2D image data.

NeuralVDB builds on OpenVDB, a storage format for large scale animated 3D voxel data. Think the output of a fluid simulation that can be included in other 3D media, for example when creating 3D animations. It was invented by Disney and is an integral part of the image pipeline of many CGI- and animation studios. Think of CGI scenes with flowing water in basically any modern movie.

OpenVDB Demo Reel, (c) OpenVDB.org

The problem is, even short sequences of high resolution 3D voxel data are just massive. You can get multiple gigabytes in less than a minute of data. OpenVDB tries to be smart and sorts and sparses the data, think run length encoding in 3D - which helps a lot.

Nvidia introduces a latent space representation of the voxels to reduce the amount of data. They use the fact, that animations have continuity. So you can a train a model on the movement of gases, liquids and solid objects in OpenVDB. Instead of storing voxels, you start with a set of voxels and store latents of motion vectors in NeuralVDB.

Image from demo animation by Nvidia, (c) by Nvidia

Image from demo animation by Nvidia, (c) by Nvidia

They claim improvements in data size up to a factor of 100x. (Or rather 1/100?)

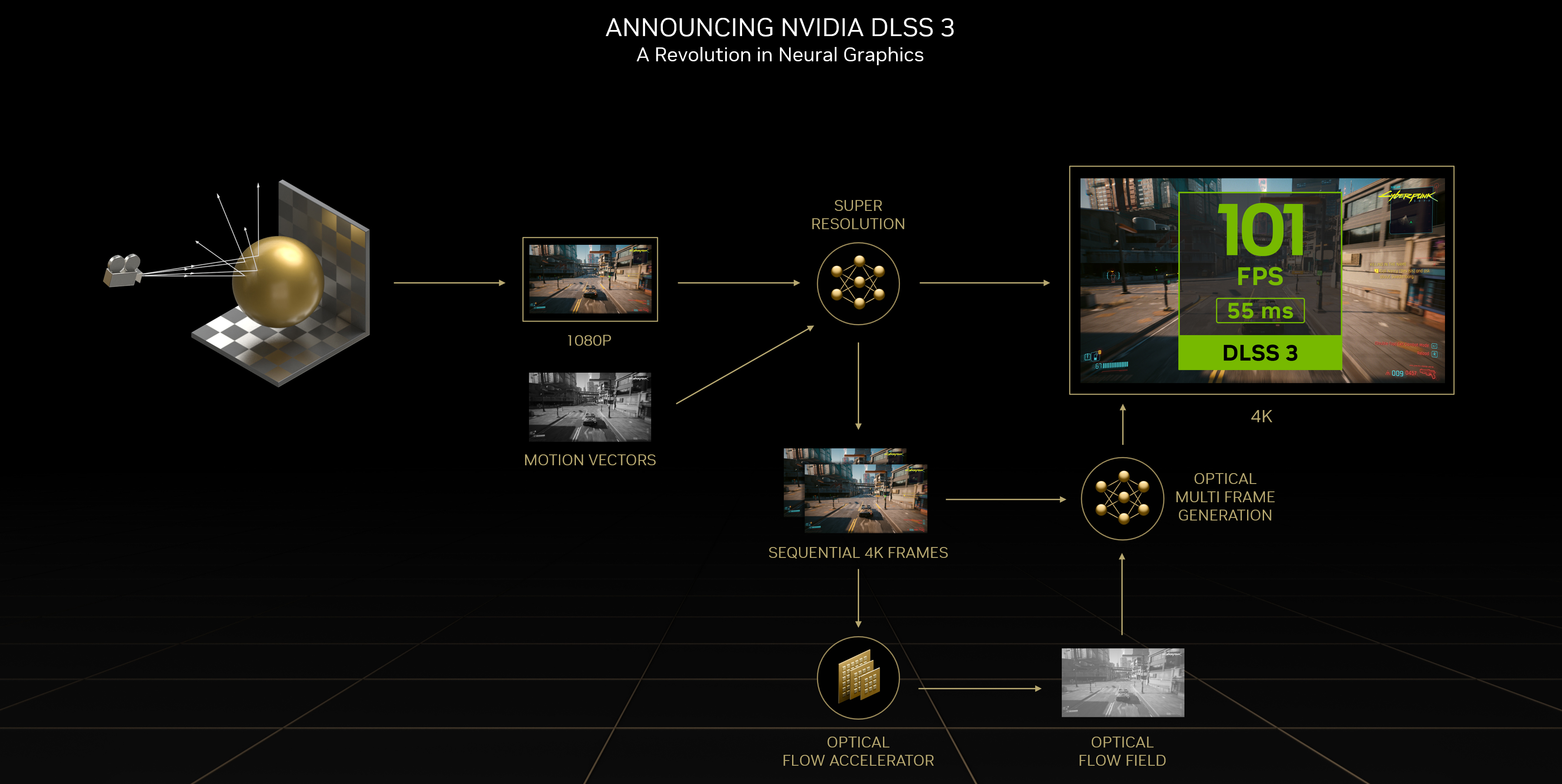

There is an obvious crossover to a different technology Nvidia introduced recently: DLSS 3

DLSS2, DLSS3’s predecessor, uses a diffusion-like model to upscale video game graphics. This is in many cases actually faster than rendering the high resolution frame using the games 3D engine. To avoid jitter between frames, it will take into account both the current low-res frame as well the last generated high-res frame.

On top, DLSS3 takes into account 3D geometry data from the GPU to understand motion-vectors in the scene’s 3D space. This allows to add one critical improvement - DLSS3 can generated completely new frames between the frames the GPU outputs and thus massively increases the game’s frames per second - without the game being actually involved.

There seems to be an overlap between DLSS3 and NeuralVDB here in the sense as both can extract motion vectors from 3D data and use it to create additional output data.

DLSS 3 visualization, (c) by Nvidia

DLSS 3 visualization, (c) by Nvidia

Possible applications / Future uses

Basically if you have a source of massive, discrete data like

- PCM audio

- images

- video

- 3D voxel data (as demonstrated)

- measurement data like topological maps

- weather data / heat distributions

basically any discrete data especially with multiple samples over time, then you can try to train a ML diffusion model on that data.

If you can create latents for a given piece of data and if a loss of some detail on the reconstructed data is acceptable, you can use such an approach to create an efficient lossy data compression. This makes it easier to store, transport and even process that data

Imagine a large fluid simulation. If you accept some error, you can use technology similar to NVidia’s implementation to create a more coarse simulation and use the ML model to interpolate/guess data in between. This can massively improve the compute time needed to visually render the simulation in addition to needing less storage/RAM. In essence you can skip/replace some parts of your simulations output and let the model guess the missing data. This can also make “digital twin” simulations of real world environments much easier to handle computing wise.

Another obvious scenario is moving images, i.e. video. It is not hard to imagine a latent space representation of 2D image data over time instead just on a single frame. The same kind of motion vector detection as already present in current video codecs and also introduced in NeuralVDB could be applied to 2D instead of 3D pixel data. This would result in an “AI supported” video codec. The needed fast reconstruction of the images on playback could happen directly on modern GPUs, which already can handle such tasks as shown by DLSS 2/3.

This was one major reason, why projects like Stable Diffusion switched to the latent space representation instead of sticking to image space. This representation is faster to work on and needs less space. The processing is possible on a Notebook in contrast to a server cluster.

Outlook

Companies like Nvidia leverage their massive catalogue of software and hardware to support those scenarios as it helps them sell. Companies building rendering software for 3D studios already work on incorporating these technologies, others including open source projects will follow.

I personally expect massive usage, not of a single product or implementation, but of this new approach to store and interpret almost any source of discrete sensory data. We will see applications in many fields including audio, video, GIS systems and fields that currently are to data-heavy to be mainstream.

Interpretation / Mushy stuff

Skip this if you don’t like non-scientific comparisons.

Studies show, language language models have similar activation patterns to human brains, when answering questions. There seems to be a similarity between the operation of a large language model and our thought process. See Caucheteux, C., King, JR. Brains and algorithms partially converge in natural language processing.

Yes, we are talking about diffusion models and not linguistic models here - I know. Also there is a strong separation between the knowledge stored in a ML diffusion model and the latent data created by an var. autoencoder.

Still - by the definition of an autoencoder: The better the model “understands” given data, the less information needs to be stored in the latent space representation. It would also make sense for brains to store only the minimal amount information needed to “remember” something.

Let us take this to an extreme. Assume a model could recreate, say, a movie’s audio and video just from mentioning the name of the movie. Then we might have created something akin to memory (as in remembering) but for machines. Like when we are able to sing along to a song we know by hard just from hearing some initial guitar chords. Like when a smell will bring back a whole slew of memories of a prior event. Streaming a movie in this case would be like tapping into another beings memories - just in upscaled Full HD or 4K.